In my 20s, I became obsessed with going off snowboard jumps1. But on my 28th birthday, I overshot a jump and tried to bail mid-air. It was not a large jump — only about half the length of the biggest Olympic slopestyle jumps. And having gone off jumps like it before, I felt confident enough to go in blind, without a plan — without riding up to the lip, without watching anyone else go off first, without doing the standard things one does to prepare to launch into the sky.

So I went in far too fast and overshot the landing by about 20 feet. And as soon as I popped off the lip, I started to panic:

oh my god the ground is too far away

oh my god the ground is too far away

oh my god the ground—

I tried to fly like a chicken for 3 seconds, then woke up in the ski clinic with a stranger asking me to repeat “trains planes and daffodils”. I complied, reassuring my wife with a quick “see I’m fine!”, to which she replied, “that was the 5th time he asked, Robert!”

I’m digressing. My objective is not to talk about the trauma imposed on myself or my friends and family in doing stupidly dangerous things2, but to point out how crippling fear can be, and how ski jump fear can prove to be an apt pedagogical metaphor for understanding fear and, more generally, anxiety. Let’s dissect what happened.

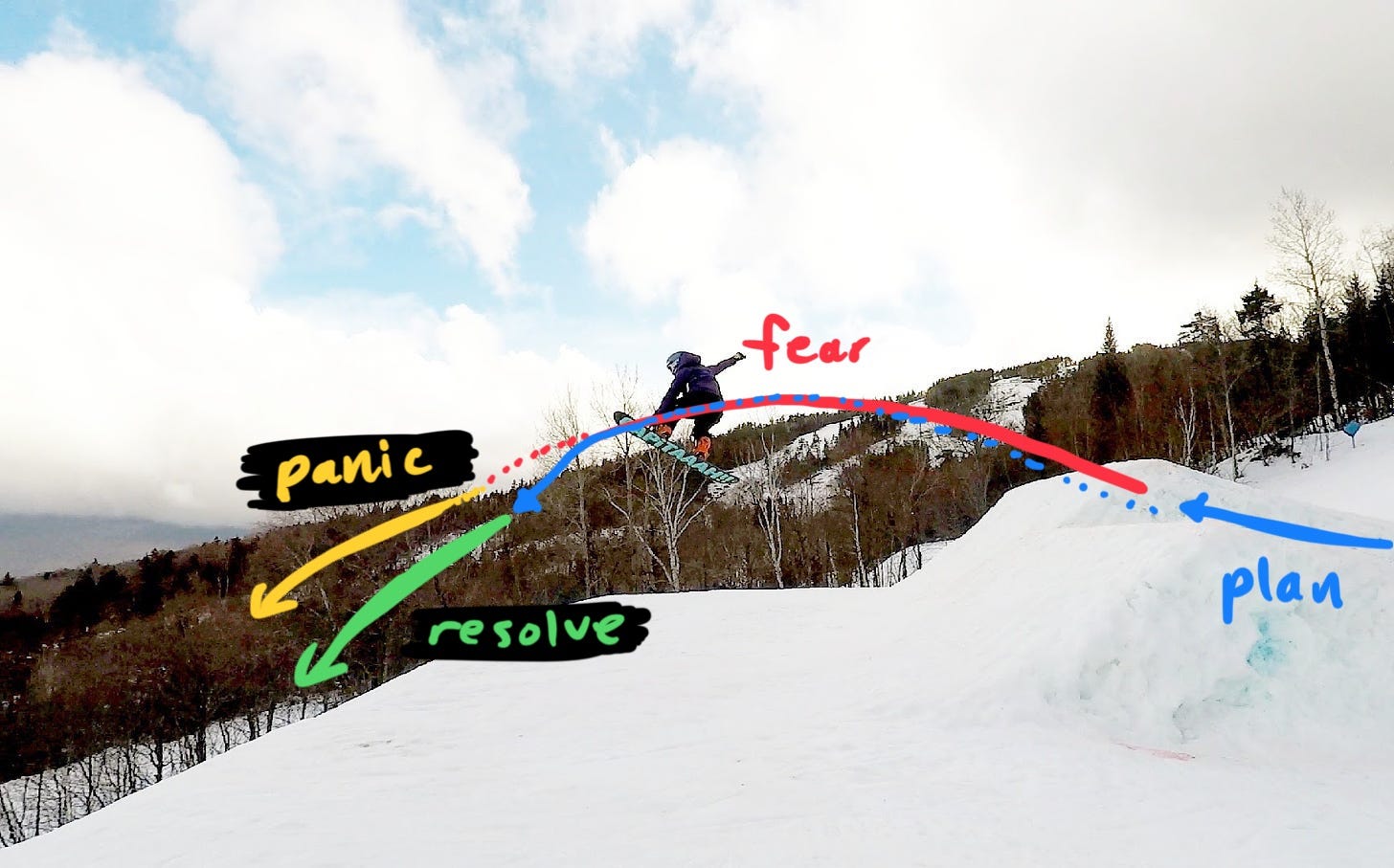

The panic arc

There’s some clarity we can get by just dissecting what happens when you’re afraid. Here’s a diagram of my emotional arc mapped onto my botched jump — it was just a direct line from fear into panic:

And I think there are two primary ways of mitigating that fear — you can either:

Reduce the difficulty of establishing resolve by starting with a plan, or

Strengthen the muscle of establishing resolve itself

You won’t think clearly if the fear is too large, and in that regard preparation can mitigate the magnitude of the fear. This was clearly the mistake I made.

But in the moment, there’s also a level of training that can bring you through the fear. A self-awareness that fear is happening, that the fear can wash over but not consume you, that you can still find yourself underneath it. And to boot, you find yourself with a greater resolve propelled by a heightened awareness you siphon from that fear state. This is a thing you can learn to even love practicing, and was largely why I loved snowboarding so much — you get to repeatedly pass through your body’s adrenal response and learn to leverage it. Adrenaline, coursing through your veins, can induce deep panic states, but when you let it course over you without consuming you, it can be empowering.

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.”

- Dune

Fear is everywhere

Snowboard jumps, of course, are an extreme example, but the response pattern is general. Adrenaline response is a distillation and condensation of pure fear into a few seconds, and as a result, bears an intensity that makes it feel different from the kinds of fear we encounter day-to-day. But fear’s nominal, low-grade but persistent counterpart — anxiety — bears a striking resemblance, and this is something that I think most of us encounter more regularly.

And, on the one hand, I’ve found that the strategies for dealing with anxiety are quite similar to those for dealing with fear. As with fear, having a plan can summon resolve in the moment, making it less likely for anxiety to devolve into a deep panic state. And, if the anxiety is still overwhelming, summoning some self-awareness to see yourself under the anxiety, under the fear, can give you clarity of thought when your body is just screaming to move. Learning to let the feeling wash over you without carrying you away can be almost pleasant, eventually. Where adrenaline can manifest as either panic or thrill, so too can anxiety manifest as either stress or excitement.

That said, I think we undervalue the utility of anxiety, and in that sense, “dealing with it” — the most common framing of anxiety narratives — is perhaps not quite right3. I’ve been watching lately when my brain falls into anxiety, and I’ve noticed it’s a strong propellant. It pulls you to do things. You find yourself in a situation that needs to change, you intuit that you can indeed exert some agency over it, and anxiety arises as the physiological mechanism that compels you to take action to resolve it. I think in the same way that you can find greater resolve beyond fear, it’s possible to find a similarly motivating determination beyond anxiety.

This might sound impossible to internalize for those of you routinely consumed by your anxiety, but I think this is because we’re so used to mapping judgment to anxiety — we value it as a negative trait, something to escape from. But in reality, it’s simply a physiological response that doesn’t inherently mean anything. And as such, once you strip it of the thoughts you have about it, it can exist as a state, like any other state — and in this way, you can either choose to let it pass away or engage with it. And if you engage with it, sans judgment, you can find yourself with greater energy to push through and get something done than those without it.

If you're covertly trying to get rid of anxiety while you are covertly trying to change it, it might go away because your attention might get divert by something else, but it's truly not an effective remedy. The most effective remedy is to be open and equanimous enough in the face of anxiety so that you recognize that your freedom isn't dependent on its going away.

(Being Mindful of Anxiety)

This has been so valuable to learn for me because fear and anxiety are everywhere, and for the bulk of my adult life, I considered it a bug, not a feature. I’ve white-knuckled my way through all kinds of anxiety about almost everything in my life, from the more obvious macro-arc things, like fear of failure, to even the smallest of circumstances — social anxiety, relationship anxiety, fear of public speaking, financial anxiety. But there’s a power to naming that anxiety, and acting in recognition of what it’s compelling you to do — to work harder, to prepare more deeply, to do what it takes to win.

And in that sense, while anxiety might feel overwhelming, it can also make it a lot easier to get shit done — there's a deep, coursing energy to it that’s hard to match. Without understanding what your anxiety is, there’s little you can do but haphazardly flail against it. But once you see it, you can choose how you want to engage. Let it pass, or ride it somewhere.

And jumping off cliffs and bridges, but that’s another story.

And if not clear, I fully recovered. Also, sorry.

Caveat: I am not a medical professional, so of course if you suffer from clinical anxiety, this is likely all bad advice.

Great article!

I agree. I have learned in my own life that when I get anxious, often times the best antidote is “action”. So anxiety does propel me to take action. (Although, I still don’t like feeling anxious).

How is it we have so much in common? Like you, I used to enjoy snowboard jumping, though I think on a modest scale. And like you, I once injuried myself going off a jump blind, ending my season.

I think a lot about stress, fear, and anxiety. Essentially the same topic. And I think about both the utility and the costs of those feelings. I like to think that stress enables us to "break the rules" or exceed our limits. Its drive exception behavior and action. The operative word is "exceptional". When you go beyond the norm, you are digging into your reserves. Could be internal reserves such as physical and emotional or external reserves such as money and friendship. The thing is, its deficit spending. Good in the short term but likely not maintainable. The research is very clear....in the long run "stress kills!".