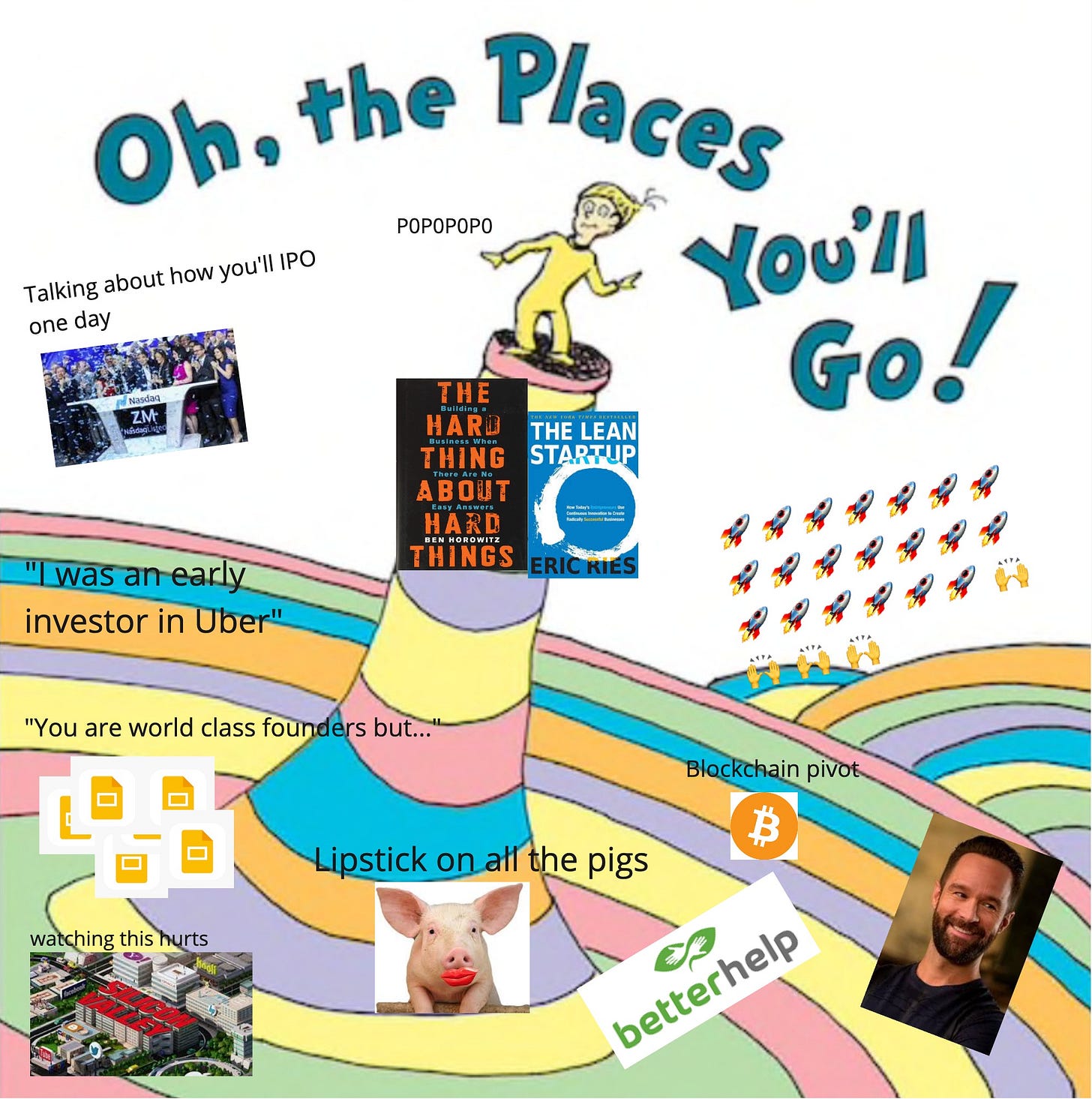

Oh the places you'll go [as a startup founder]

The five stages of startup delusion: denial, denial, denial, denial, denial

I’m going to tell a story of what it’s like to build a company. Some of the mistakes I’ll share I made myself, some of these I observed in others. I’m sharing this because I noticed that very few people are able to convey what building a company will actually be like, and folks considering embarking on this journey are often stuck stringing together an understanding from trite aphorisms (“execution is everything”, “build something people love”, “shoot for the moon, even if you miss…”), ominous warnings (“it will be hard”, “be prepared to make sacrifices”), and TechCrunch-colored narratives. So I hope this can give you a deeper glimpse into the nature of not only why it is hard, but also why it is such a uniquely exceptional experience. I’ll start with a story, but if you want to just get to the takeaways, you can skip my meandering bard’s tale entirely and jump to the bottom.

A caveat: the lessons and commentary are only really applicable to venture-backed startups, not so much traditional SMBs.

The story

Stage 1: Vision and lies

One day, you come up with an idea. You think it’s a great idea. An excellent idea, perhaps. You read some quotes from Reid Hoffman and Paul Graham and find yourself nodding along, so you decide to start a company. You plow through a “how to build a company” checklist you got from Google/ChatGPT, feeling more and more empowered as you go: you set up a domain, start a Notion workspace, incorporate a Delaware C-Corp. And then you buckle down and get to work, spending your evenings building a prototype on your [non-work] machine. And it’s fun — you’re in flow until midnight every day. Progress is addictive, and after a few weeks you’ve built a respectable prototype. It feels good to build something with your own hands, owned entirely by you. The world opens itself to you, rich and wild and full of possibility.

You decide one day that your product is good enough to show people, so you begin looking for customers. You start with your friends (“design partners”) and they claim they “love” it, but really they value your friendship far too much (but not enough) to risk it with truly honest feedback. And validation is what you secretly want to hear anyway. You’re looking for the dream to keep floating along, unchecked, buoyed by a healthy dose of confirmation bias. Propped up by their optimism, you launch, and some people even buy your product. Perhaps it’s not confirmation bias after all, and your last shred of honest skepticism is buried beneath layers of ego and artifice.

And you figure if you can believe it’ll work, so will the rest of the world. So, filled to the brim with gaslight, you puff up your chest and begin to spread the gospel. You launch, repeatedly. You build up hype. You take irreverent stances on Twitter. You get quite a few eyeballs, some of which are excited potential investors, so you take the opportunity to raise capital.

From your first few investor calls, you find out that there are products that already exist to solve this problem, that your vision is not particularly compelling, that they don’t think this is going to work because they don’t understand what you’re doing, as much as they like you, etc. etc. But you tell yourself “they just don’t get it” and double down on your esoteric value proposition. You come up with more elegant arguments, you improve your ability to speak concisely and extemporaneously respond to increasingly predictable investor questions.

And with enough hits at bat, some investors latch on — you manage to raise some pre-seed/F&F/seed funds. They run due-diligence, talking to your design partner friends, who have nothing but wonderful things to say about you and your product. Money comes in, and as soon as you see the cold, hard cash hit your bank account, you take it as validation that all your ideas are correct. Confirmation bias thickens the white matter of your brain, so you forge ahead, bolstered by dopamine-rich validation. Your competitors are doing great, after all, and you have a better product.

Stage 2: Going Through the Startup Motions

You read a tweet somewhere that execution is all that matters, so you don’t stop for a second to think whether any of what you want to be true — what you’ve convinced yourself to be true — is actually true. You take the advice as sanction to silence your brain and feed your flow addiction. Still, you struggle to find customers that love you, so you pile feature on feature, hoping that the next one will bring your product to take off like wildfire. To sustain that iteration process, you desperately follow the “build fast, break things” mantra circa 2015, tripping over yourself to ship. Naturally, you take on heavy amounts of tech debt, but “tech debt is a strategy”, after all. It’s a little painful to build such garbage, but fortunately, you’ve heard it said that “if you’re not embarrassed of your product, you shipped too late”, so you know by that metric you’re shipping right on time, every time.

You do all the standard startup things: you hire a team, write OKRs, hold lavish off-sites in the name of “brand”, and otherwise perform a watered-down reenactment of HBO’s Silicon Valley. Unfortunately, you still have no customers, and your first cohort has churned entirely — you’ve exhausted the patience of {your close friends, investor intros, other startups in your incubator}, and you realize you have to get a proper lead generation process working. You try cold calling, emails, social media marketing, blog post writing. You hire advisors, marketing experts, hoping you can outsource your problem.

And sometimes, at this point, your death is written, for sometimes there is no path through. And in all likelihood, you’re missing the mental fortitude to untangle the web of fallacies you’ve constructed, to take ownership and responsibility for the decisions you’ve made — whether explicit or not — to accept that you not only can but are failing and need to pivot, in some shape or form. You’ll instead push harder and harder with Sisyphean futility until you’re ultimately forced to face defeat. But still, in all likelihood, your ever-resilient narcissism will spin the loss to protect your ego — “you learned so much”, “the market was just not ready”.

Stage 3: Getting to PMF

But for some of you, either as a result of gut-wrenching pivot(s), sheer luck, or some combination thereof, something eventually sticks, and you establish a steady trickle of customers in. Hallelujah! You’ve validated that you might deserve to exist. But unfortunately, that’s all. For still, through this process, you eventually come to the realization that you have not reached PMF, in spite of the 5 happy customers you have. Because something’s still not quite right. Because hundreds of failed sales calls later, you realize no one really knows what you’re selling — not even you.

You iterate on positioning, on marketing, on your go-to-market engine. And if you have not come to value intellectual honesty at this point, you better figure it out fast, for the iteration cycles need to come rapidly and with a healthy dose of brutal, honest scrutiny. You try dozens of different GTM motions and tweaks, sourced from hours of Lenny Rachitsky interviews. Your copy varies wildly from the onerously specific (“SALES DATABASE WITH SOCIAL MEDIA INTEGRATION”) to buzzword bingo (“ALL-IN-ONE SALES PLATFORM FOR KNOWLEDGE WORKERS”). But as the creativity faucet finally purges itself of crud, you unearth a laser-focused value proposition: “Modern CRM”. And the sales calls go substantially better. And suddenly, some (even many!) of your GTM systems start to work. You have leads, and they are converting.

Stage 4: Rebuild

If you’ve been following the advice of late 2010 startup content until this point, this is usually when you’ll realize that your shitty architecture is coming to bite you in the ass. Your product is compelling, but it’s unstable. Your engineering strategy was built on faulty platitudes. And by direct consequence, while you can sell the product, few will tolerate it long enough to use it. You spend months (or years, or forever) trying to crawl out of that hole. You set up a p0 Slack channel that is so constantly full of alerts that your team — you — burn out. Why is your team so bad? How did we get in this situation? Well, the answer is clear: you fucked up. “But we had to!” you say, but you’re just avoiding the truth that all of your knowledge of company-building came from Twitter, and most of it was profoundly wrong for {this point in time, this product, this industry}.

For the truly honest few, you own up to your mistakes, think from first principles about how to solve the problems you’re facing, and have enough capital less your launch parties or domain name expenses that you can rebuild the product and team correctly. And it all finally works. It’s stable and loved. You have a repeatable lead gen motion, a steady conversion rate, net negative churn. You rejoice! You know you have a business because your first 100 customers love your app, and if 100 customers exist, surely thousands — nay, millions — exist.

And so you forge ahead. You raise a Series A, even a Series B, with a deck full of optimistic projections based on your current growth. With fresh funding, you’re off to the races. Everything works, you can relax — you just need to 10x, 100x everything you’ve been doing. You go to conferences, you hire social media influencers, you start a Slack community, you host webinars, you buy absurd swag. The world seems primed for a takeover — you, inc., the next unicorn, decacorn, even.

Stage 5: Face what your lies have wrought

For the lucky few, scale happens. But for many, here is where your first deception comes to call: you’d convinced yourself and your investors that the market was huge, but is it, really? Can you really unlock $60B of “knowledge worker” value? No one can blame you for believing it was when you started the company — everyone else did, after all. But the growth seems suspiciously slower than you’d like. It feels as if all your best efforts are just barely enough to reach parity with the initial burst of revenue that fell into your laps when tailwinds were favorable. The hockey stick was certainly a hockey stick, but by your projections, the slope of the handle is enough to reach unicorn status in about 30 years. You could’ve invested your fundraise into the S&P500 with about the same outcome.

So you make asymmetric changes, hire tried-and-true tech executives, crank up the revenue machine, all the while cautiously watching new bright-eyed seed founders slice up your market further. And while you know that you can hold your ground for now, you know it’s only a matter of time until that changes. The ever-growing open source world will spawn new, more cost-effective starting points every year. The underlying infrastructural options will only get faster. And the sheer number of founders will abound to a point that it becomes a statistical inevitability that one will subvert you, take your place as zombie king, and force you to exit to private equity.

For that is what you are now: a zombie company. So you have a tough choice to make — sell your business, perform an unprecedentedly dizzying pivot, try to SPAC, or rebuild as a “lifestyle business”, dragging investors along on your zombie company leash.

The lessons

Lesson 1: Some things matter more than others.

The most harrowing thing about this story, in my opinion, is the brutal inevitability of the outcome. Your grit, your ingenuity, the good fortune that you happened upon, your hard-won personal growth — none of it mattered in the end. Because the zombie company outcome was a consequence of a single decision made early-on: choosing the wrong space. No matter what transpired between inception and exit, the bounds of your fate were largely sealed by that one choice you made around what to build, decided when you were the stupidest.

Ergo, the single-most important thing to take away from all this is that not all decisions are made equal. Existential decisions — like your choice of market, your choice of team, and later, your choice of architecture — can make or break you. But others — like where to have your offsite or how you should structure your meetings — will generally make no difference whatsoever, but are still easy time sinks. Fortunately, the remedy is simple: just focus on getting the right people working on the right problem, and remember that focus is about saying no.

“It doesn't matter how amazing your product is, or how fast you ship features. The market you're in will determine most of your growth. For better or worse, Gumroad grew at roughly the same rate almost every month because that's how quickly the market determined we would grow.”

- Sahil Lavingia, “Reflecting on My Failure to Build a Billion-Dollar Company”

Lesson 2: Intellectual honesty is the only thing that will save you.

Of course, even with that knowledge, you’re going to make the wrong decisions, even when it comes to the most important ones. Even the best of us can only see so far in the fog. And the only thing that will save you from those mistakes is brutal honesty. Did you really hire the right people? And did you really choose the right space? These two in particular are the two most difficult questions to ask, particularly because addressing errors against those decisions is so painful: you’re either going to have to fire someone or pivot.

But it must be done. To counteract the immense amount of pain this might cause you, you need a commensurate commitment to intellectual honesty. And if you’re able to maintain that commitment, you’ll be fine. For as fatalistic as I sound, bad decisions are rarely catastrophically bad — they only become truly catastrophic when you gaslight yourself into believing that they were actually good decisions, allowing their consequences to unfold and ramify, unchecked.

Final points

I hope some of this was helpful, particularly if you’ve ever thought of starting a company. Before founding my first company, I held only this vague notion that it’d involve primarily bracing myself for the folklore of entrepreneurship: sleepless nights, 18-hour days, mental exhaustion, constant uncertainty. And certainly, those things would come. But those are only common patterns of behavior, not to be confused with any sort of methodology. I believe this misconception (and many of the failings listed above) stems from a perspective common in the startup world that building a startup is all about execution, but this advice is often warped into sanction to act (“hustle”) without thought.

But here’s the thing: companies aren’t MMOs. You can’t mindlessly grind your way to the finish line. The game is one where you must think about what you should do, then do it. There’s an element of expediency involved, but that expediency cannot be undirected. Sometimes the best thing to do is live in the factory for 3 years, but only if you’ve determined that the best thing to do is to live in the factory for 3 years. You can’t just live in a factory for 3 years and expect to conjure Tesla. Doing painful things that do not drive the needle is pointless, toxic self-flagellation optimized for virtue signaling, not success. As heroic as these stories might sound when recounted by successful founders, they’re byproducts of dedication, not a recipe for success.

Startups are about honesty. Pre-PMF, your job is primarily to repeatedly form hypotheses then gather data to test them. Rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. Action is sometimes the rate-limiting step, but in my experience, most people who want to start a company know how to work hard. So more often, you’ll find that you’re rate-limited by your capacity to confront and think about the truth. Of course, sometimes it’s hard to, psychologically traumatizing, even, but if you’re not willing to do it, you should seriously reconsider whether you should be building a company, or your story may ultimately look not so unlike the one I just laid out for you.

Such an enjoyable read! I love the way you structures and phrased it, and it rings quite true.

I think the single most important quality for an entrepreneur is to follow your convictions for as long as you can, but no longer. When reality shows you a different path, grab the wheel and pull, and take it.

Clinging to beliefs for emotional reasons is deeply human, but it seems to be a shortcut to painful failure. Or maybe a longcut, if you’re resilient enough to take a beating or two (or a hundred).

I’d love to hear about specific times when you had to recalibrate and face the truth, and how you decided it was time to do so. That is a hard skill to hone. Because how can you ever know? I think it takes analysis and re-analysis over and over—a lot of our talking heads tell the same stories about the same events, year after year, but are those stories even true? Or did they find a convenient lie that sounds good (I.e., execution is everything), and they get applause for repeating it, for the rest of their tenure?

Sounds like a boring life.

Anyway, I appreciate your post! Definitely excellent food for thought.

thanks for sharing! I can relate to some of what you went through and not just in the context of the startup experience.

as I've grown older, a recurring realization I've had, so deceptively simple is something like: self-honesty is the bedrock of a good life. it's the main (only?) practice that allows us to course-correct when misled by our lizard brains and fragile egos. but it's also a practice that requires attention and cultivation.

I think one thing that's required is distance. as long as you're deep in the thick of the tumult, it is extremely difficult to have a clear perspective on what you're doing wrong. the more habits you can cultivate to give you distance from your situation - whether mentally thru writing or meditation, or physically through exercise or just being out in nature - the more likely you are to find the space for self-honesty.