Playground, not stage

Refactoring our default motivational pathways

On a stage, you perform. It can be a wonderful thing — an elegant distillation of months, years of work. You’re offering a rare glimpse into your heretofore shuttered imagination. But in every performance, the performer inevitably carries an acute awareness of what others think. The performance accumulates its most palpable value through grants from the audience, after all. And when that incentive pathway etches deeper, the performance becomes the means by which to maximize praise, rather than a reflection of something intrinsic. It’s not inevitable, of course, but the bias is surely there.

Playgrounds are wildly different. You do you. You build castles, you dig holes, you bury leaves and make messes. Most of what you do is terrible, but sometimes wonderful. Your curiosity is driving, not your hubris, so of course, you find things you can’t find on a stage. Most people wouldn’t want to watch you play in a playground, so value proposition remains intrinsic, by and large. Again, not incorruptible, of course, but the incentive structure is certainly preferable.

I think all of us tend to view the world as a stage to some extent. It’s deep-seated within us to care about what other people think. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing — it can be noble, even, particularly when your work is in service of others. But there is this curious tendency for this incentive pattern to warp (and ruin) the best of us.

In general, I believe life is better approached as a playground.

We all start on a stage

I think everybody starts on a stage. We need to establish base value assignments to things in the world, and as children, I suspect we do this largely through mimesis — we internalize the value attributed to things by observing those around us. And inevitably, we look to these people for their validation. Our core values become this mix of the values of the people around us.

In fact, we can extend this concept to everything in your life, up to a point. Everything is given to you in the beginning. You are plopped into a life that you neither designed nor [in all likelihood] desired. Initial conditions are set without your consideration, and the mimesis ramifies and elaborates until you mix your arbitrary upbringing with the present cultural ethos. We commonly think of opportunities and circumstances provided by our parents as falling within this scope, but without your own internal value system, so too do all of your actions.

And so, you establish a hornet’s nest of mimicry instead of a deep, internal understand of what you want. And often, this can become quite distorted. Your innate, legitimate (but quiet) need for friendship and understanding turns into a need for external validation met by Instagram follower count. The wonderful, beautiful capacity of your mind to compose rational thoughts turns into some warped need to be perceived as smarter than others. There are some things that we all instinctively know are of inherent value and we, as humans, find deeply rewarding, but above them we stack layers on layers of want and need incepted in us by our circumstances, our genetics, our parents.

And so, inevitably, we all start on the stage, addicted to the drip.

Tearing down the stage

So here’s what happens next: unfortunately, most of us attain some modicum of worldly success — we graduate from school, we receive some recognition, etc. etc. And so we kick the self-awareness can down the road. We continue to maintain the dopamine drip by reinforcing the circumstances that led us there — the circumstances that have been, unfortunately, shaped by others.

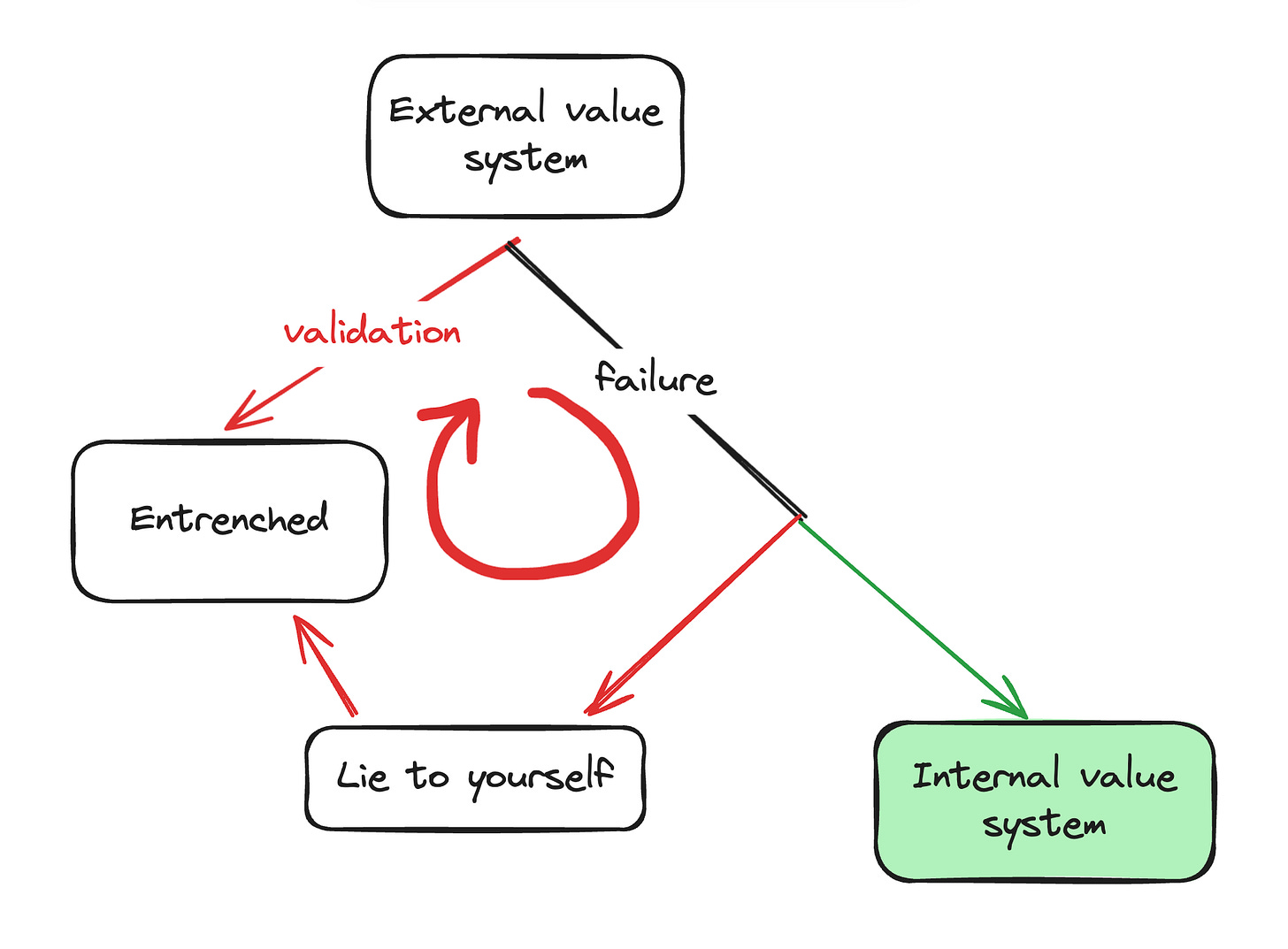

I think, generally speaking, there are two paths to reaching escape velocity and refactoring against an internal value system: through failure, or directly through careful self-reflection. With failure or trauma there’s a chance of mustering enough self-awareness to establish your own internal value system. But only a chance. Inadequacy will always creates one of three things: change, acceptance, or lies. And lies are dangerous here — oftentimes, we’ll internalize plausible lies (it was this other person’s fault; I'm brilliant enough I just don't work hard). And so you end up with a string of half-truths and motivational quotes papier-mâchéd over your reality.

But of course, direct reflection can also directly get you there — it’s just that most people aren’t motivated to reflect except through suffering. The key is to dissociate yourself from the arbitrary stimuli that are guiding your actions (including the default external value system that your brain has latched onto). At the end of the day, it all comes down to mindfully living. Being directed by your own value system vs. an external one is the difference between summoning clear intent and, effectively, being lived.

The playground mentality: you don’t need to do a thing

I recently read a wonderful piece by Alanna Duffield. She talks about finding new “mundane” hobbies after her father became ill:

“I wish I’d spent more time with my family. I wish I’d lived a life that was true to myself, not what others expected of me. … In a world that wants us to be permanently cool, glamorous, wealthy and good-looking, it can feel revolutionary to prioritise slowness, learning, human connection and the natural world.”

I think there’s something profound in realizing that you don’t have to do anything. There’s this beautiful Mary Oliver poem that a good friend shared with me years ago:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

- Mary Oliver, Wild Geese

I remember when I first read it, I thought it a call to inaction — a proposal to drift dreamily through life, to accept your place as a goose. But I now understand it as quite the opposite: it’s an articulation of why we strive. It’s a means of toppling the narcissistic inclination that comes with any sort of effort/success and replacing it with something genuine. Start with nothing — you are a wild goose, after all. Only then can you relish the way the world offers itself to your imagination. We shouldn’t create to win, we should create because it’s wonderful that we can.

Such a great piece and thank you for the shout out! ✨