I recently read a great post from

, where he claimed that the constraints on successfully exercising are largely emotional. He spends some time talking about this book about exercise, and quotes a particularly compelling review of the book:“I fact checked the book and found the exercise claims solid, but when I gave the book to 6 people none of them exercised more.”

Of course! Of course reading a book that extolls the virtues of exercise does not make you more likely to exercise. We all already know exercise is good for us. That’s not the blocker. The blocker is entirely one of motivation.

And there are so many books in other categories just like this — I think this is why people roll their eyes so often at the self-help book category. Yes, I do want to be healthier. Yes, I do want to think better1. Yes, I do want to adopt the 7 habits of highly effective people. But of course, knowing what to do is a very different thing from actually doing the thing you know is what you want to do.

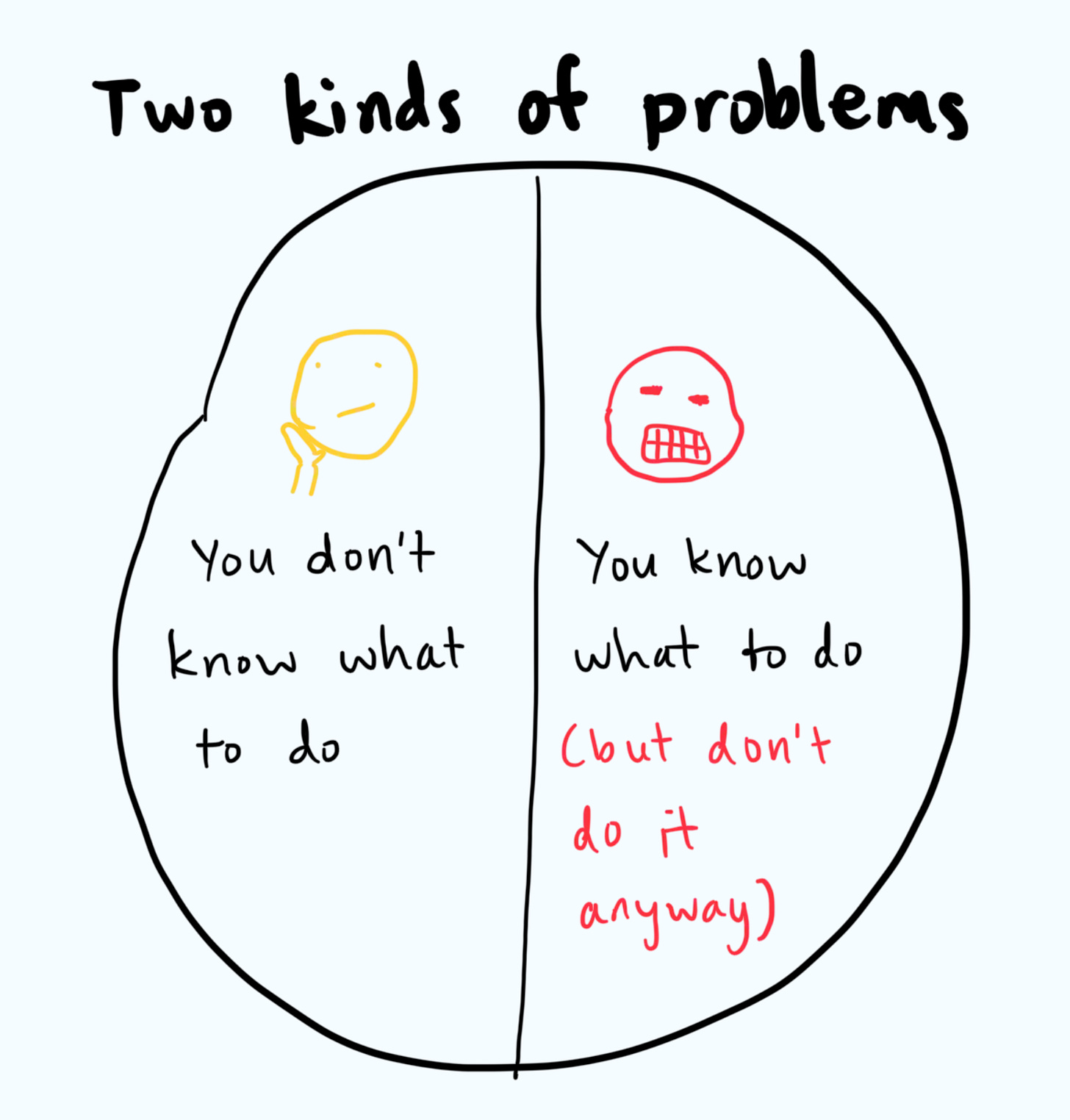

I think you can divide problems into two categories:

Problems where you don’t know what to do.

Problems where you do know what to do, but don’t want to do it.

Let’s talk about type 2 problems.

The anatomy of not wanting to do a thing

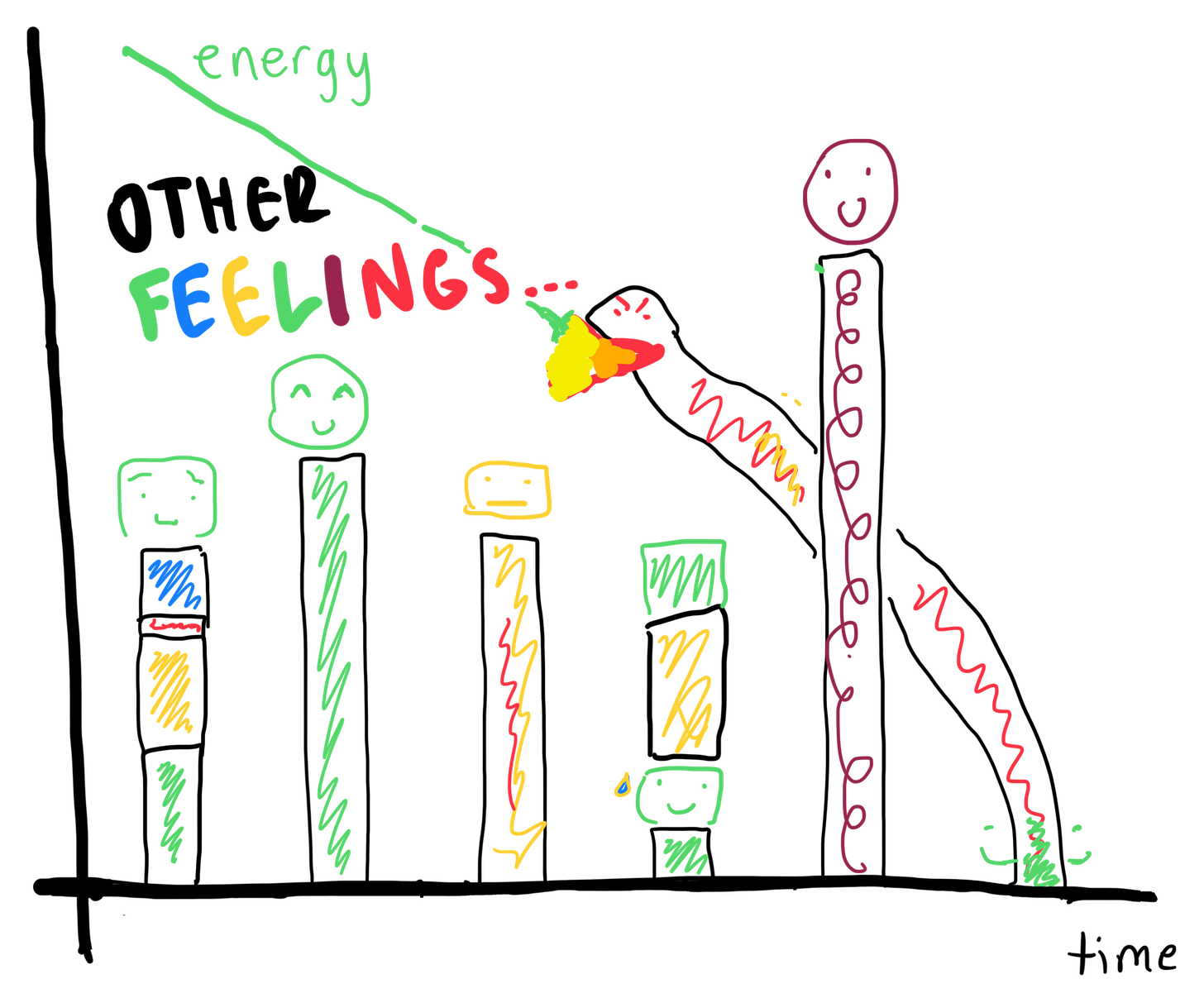

So why don’t I listen to my own advice? I think it’s tempting to oversimplify the underlying mechanism as something like this:

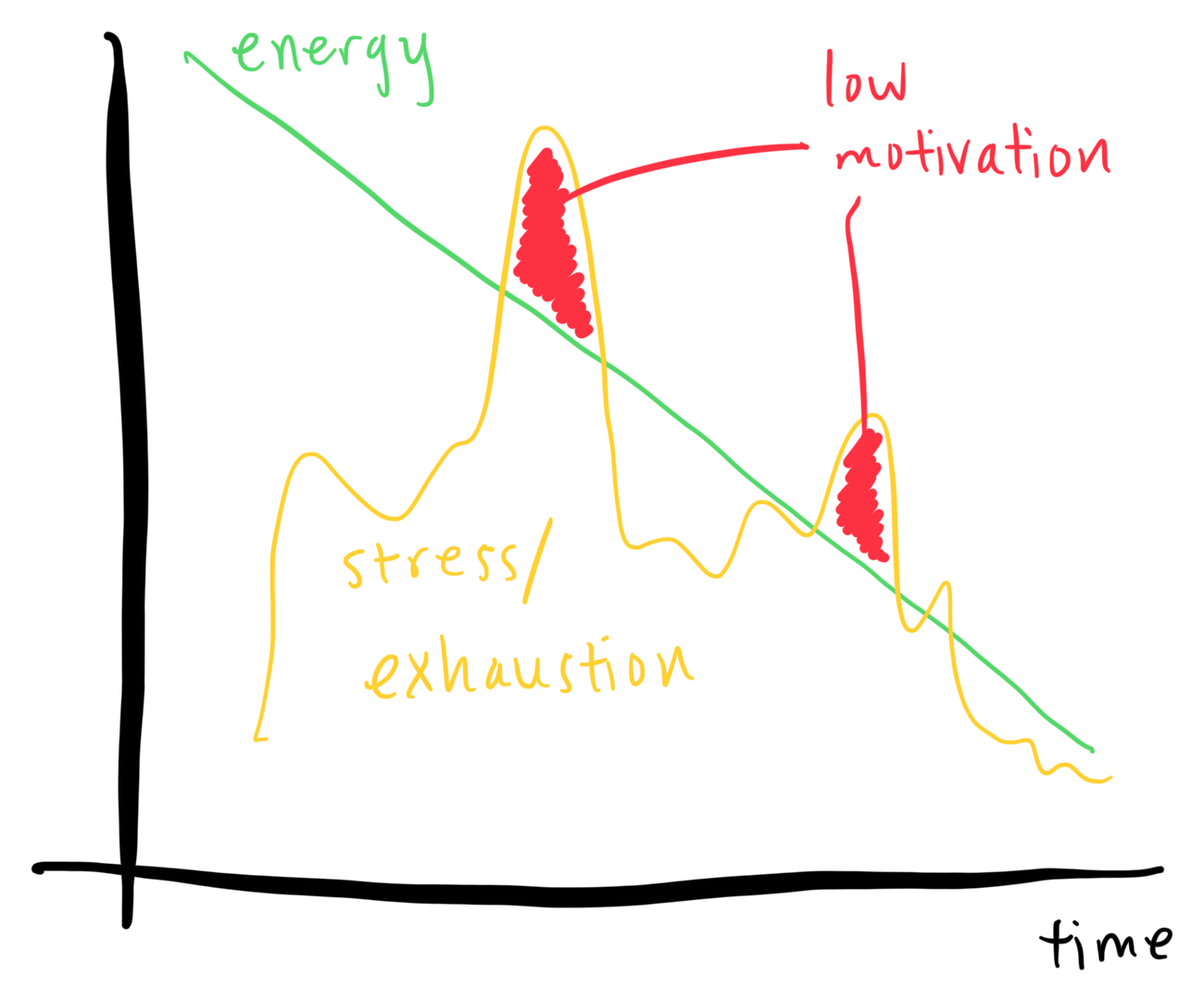

A few years ago, I went through the futile exercise of trying to map these two curves out in excruciating detail — to identify triggers of ebbs and flows so that I might appropriately titrate my caffeine intake and energy-giving activities, solving the problem of procrastination altogether. Of course, that was a complete and utter failure.

I think the issue is that reality is a bit more complicated than that. And to smush all the complexity of human emotion (and consequently, inhibitors of motivation) onto a single “stress” axis is too lossy. At any given moment, you of course don’t just feel something as simple as stress or exhaustion. It’s this assorted mix of feelings. Looming tiredness. Lack of motivation, felt as a heaviness in the chest. Stress, manifesting as a buzzing in the head. A broken thought loop where you obsess over the person that didn’t fully stop at the stop sign and almost hit you. Rage at your coworker’s mistake, but mostly hanger building as an all-consuming emptiness deep in your core. It’s a mess.

Looking at it gives you space

If you’re like me, you’re probably tempted to try to understand how this soup of emotions boils down to a binary signal — motivated or not. When am I angry? When am I happy? What seems correlated to better performance? Can I hack this in any way? But I’ve started to think this is the wrong approach. You can map out your life all you want, but the possible mixtures of feelings and stimuli that can bombard you on any given day are too infinite to fall neatly into some universal theory of motivation.

However, something that has helped me is using my periods of low motivation / high procrastination as moments to practice mindfulness — and in doing so, notice the physiological signature of that lack of motivation. Not the cause, mind you, which often just leaves me spiraling down this deep rabbit hole of revisionist history. But that tension in your head. The heaviness in your arms. The slight buzzing around your temples.

I’m not certain why it works, but I suspect by simply becoming aware of any cognitive blockers that keep you from taking your own advice, you learn to stop identifying with them (they are not you), and you thereby gain some modicum of power over them — it’s easier to fight a thing if you can see what you’re fighting, after all. And it seems like this is a legitimate effect, not just my anecdata: mindfulness can improve one’s intrinsic motivation, and I’d wager that the mechanism comes down to creating this sort of mental space to gather some willpower.

Brain rest

All that said, that often isn’t enough for me. Sometimes I feel like not doing a thing, and I see the feeling that’s getting in the way of me doing the thing, then I don’t do it anyway. For a month or two earlier in this year, I managed to combat all of it, but ended up feeling utterly drained and foggy, and I generally felt that my mental performance against critical problems was going down, even if I was “productive” all day.

Lately, my daughter has been learning piano, and sometimes during a lesson, I’ll see her think deeply about a question her teacher gives her. “What note is this?” After a 10 second, mind-grinding pause, she’ll say the right answer: “G”. And then promptly after the lesson, she’ll complain about everything. Her personality will 180 — she goes from sweet little girl to tear-down-everything-tyrant. And I’ve seen this story before. When I overwork my brain, there’s this level of cognitive exhaustion that follows.

I think to some extent, your brain needs rest. And metaphorically this makes sense — when you exercise, growth happens during rest, so rest is as important as the actual act of exercising itself. The same must be true of your brain. And certainly, the scientific literature supports this, at least within somewhat contrived environments: adding a mid-task break to a task, for instance, significantly improves subsequent performance on that task.

Of course, it’s a fine line to walk between letting your brain do what it wants to do and binge-watching Netflix all weekend. So one of the most difficult things to figure out is: what counts as a break and what doesn’t? What are the [action, break] activity pairs that work optimally together? In the end, I think we all have this tendency to view our brains as these infinite reservoirs of intelligent thought, but I think this is often more harmful than helpful. This kind of stance compels us to exert ourselves in ways that are tantamount to trying (and inevitably, failing) to exercise all day.

Final comments

In general, all I want to say is:

It’s hard to follow your own advice.

Mindfulness can help in the moment.

Breaks can help recharge you.

But my main point is this: I don’t think we collectively spend enough time understanding why we’re not doing what we want to do. We tend to chalk up poor motivation or procrastination to our own intrinsic deficiencies, but even if that is, to some extent, the case, I think you can go a long way by just scrutinizing it and seeing what you can find.

Oops, maybe.

Very well-written and SUPER relatable.

This is so interesting! Makes me think a bunch of thoughts.

First, on exercise, I have found that enjoying the feeling of exercise and the endorphins that result is the key to coming back.

I took my sister to the gym every other day for a month, and that encouragement and gentle consistency was enough for her to go from "yuck, this is so painful" to "yum, this is so painful."

There is a kernel of pleasure, joy, and satisfaction in exercise. And it can be different for different people — some for who weightlifting is always yuck might find cardio to be a godsend. In my case, it also took me time to learn to love cardio, and I still have to push myself to do it, because I'm large, lumbering, and slow. But, I can still find the enjoyment there, too. Have to dig a bit.

On energy levels, I'm surprised to see that your self-analysis was a complete failure, here. I did something similar, examining my energy and trying to figure out how to make it sustain throughout the whole day. I did find defeat there, too.

But what I realized more recently is that I'm an energy addict, and I use caffeine and hype to boost my mood to avoid the lulls or bad feelings. It became a "chasing the dragon" thing where I would pound a third or fourth coffee because I wasn't feeling "good" enough, and the feelings of frustration, doubt, or disappointment were creeping in and peeling up the caffeinated veneer.

After that, I realized that my "mood" and "fatigue" were two separate levels. My physical tiredness/fatigue is directly correlated to sleep — amount and quality — and my mood is *based* on that, but highly dependent upon brain chemicals, thoughts, and other stimuli.

To survive and become more effective, I'm trying to allow myself to operate at a lower baseline. Not using mood boosters (blue sky thinking, caffeine, etc) to give me enough energy to get over the hump of feeling things I don't want to feel or doing things I don't want to do. Plodding along *is* progress, and it's safer and more sustainable in most cases. There might be time that calls for drastic, energized action and focus, but if that's your norm, you might be doing something wrong like me.

Sort of if a team is always putting out fires. Something is dysfunctional.

Hype can be good. Constant hype is not so good...in my experience.

> Looming tiredness. Lack of motivation, felt as a heaviness in the chest. Stress, manifesting as a buzzing in the head.

This is the type of state that I instinctively reach for coffee or hype to help push through. And then it just comes back heavier and harder.

Funny you said that the cognitive blockers are not "you." On the one hand, I agree. What "you" are is really hard to pin down, but I would say it isn't really anything *in* your experience. "You" is probably the meta layer, the substrate on which the experience manifests.

But, from a more practical front, the idea that you have to "fight" cognitive blockers feels a bit too aggressive. This isn't some foreign entity invading your body/mind. It's a manifestation of your experience, conditioning, and emotions, and as a result, the best way to resolve it is to accept is. Don't resist. Just acknowledge how it feels and accept that that's actually how you feel.

I'd say that's what mindfulness means — just noticing — so I'm more just taking issue with the phrasing than your actual methodology. I think that's totally on point. The best thing to do when you run into resistance is to slow down, not scheme and grind and try to push through. Same thing you'd do with a team member who threw an objection: listen to them, acknowledge where it comes from, and give them the space and time to resolve the disconnect. You get a much stronger bond, that way.

On cognitive fatigue: it's totally real! And the more we push ourselves through it, the less we can see and control it when the bill comes due. That sort of thing can have disastrous cumulative effects. When we are in overwhelm (even when it's not obvious to us), we often make terrible choices, and undermine ourselves. It's good that you noticed that in your daughter! This is a great time to help her notice what's going on in her, and to teach her the effective strategies to monitor it, proactively recover, and take some space when she does spill overboard. Lucky!

For me, breaks mean cutting off stimulation (which is hard, because it's my default go-to). No YouTube, HackerNews, Twitter, etc. Actual quiet downtime between screens is hard to do, but it really, really helps. I love taking long walks in the flower-heavy part of the neighborhood.

Great post! Thanks for the stimulation!