Metrics, but for life

Win life with data.

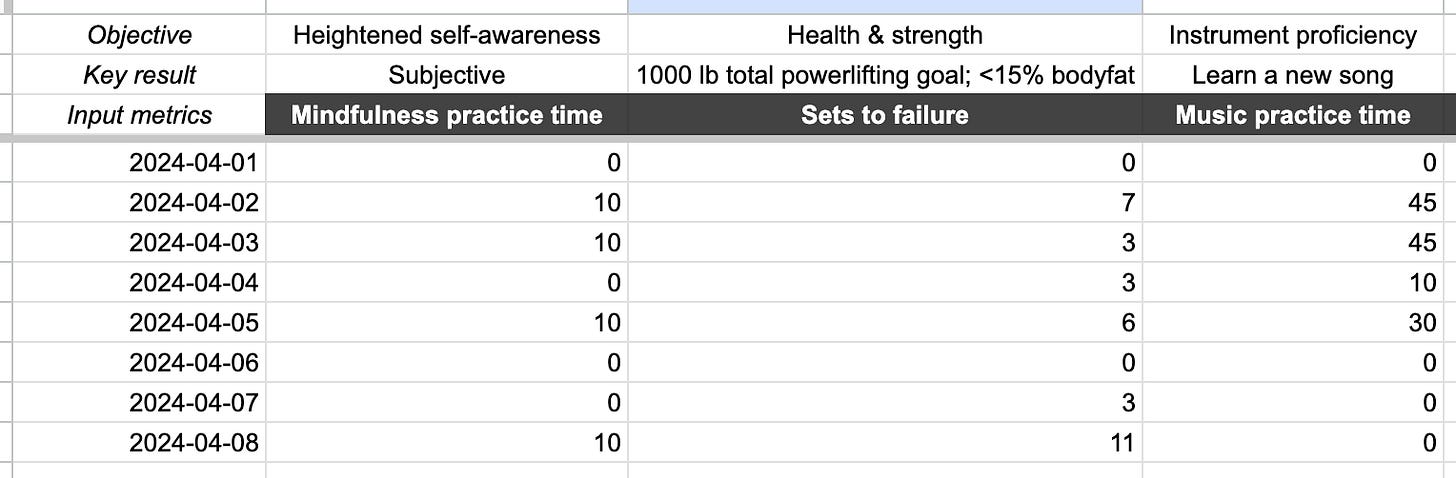

There’s this formula in tech companies for how to move things forward — define objectives and key results (OKRs), then track metrics to measure how you’re progressing towards those results. Of course, as with any framework, OKRs to be an attractor for malicious compliance, and you’ll find no shortage of disgruntled product managers shoehorning their work into objectives and measurements that justify what they’re already doing, rather than actually thinking about what would be impactful. But I digress — I really don’t like how people usually implement OKRs, if you couldn’t tell, but that’s a rant for another day.

Gripes around faulty execution aside, the underlying ideas behind traditional OKRs and metric-tracking are powerful. That said, there’s more than enough written about OKRs in the corporate world — I want to talk about how this sort of intentional goal-setting process can be helpful for individuals. In particular, I’ve taken to applying these to my personal life lately, and I’m realizing how grounding this whole thing can be. There are a few concepts I want to talk through:

Setting an objective

Finding the right input metrics

Tracking

But in short, I’d like to say that being a little bit more intentional in thinking about objectives (what you’re trying to accomplish) and metrics (what it’ll take to get there) can go a long way. Yes, yes, it might sound a bit obvious, but stay with me.

Setting an objective is first.

There’s something really valuable about learning to keep the main thing the main thing. If you have an objective in mind, everything else falls into place. It may sound trite, but it’s surprising how quickly one’s primary objective can be subverted. On the one hand, our animal brain tends to distract us nearly all the time. But beyond obvious distractions, by taking on any other perspective — not even bad ones, necessarily — you relegate your primary objective to a secondary one. It’s surprising how easily something else can become the main thing.

I think this is why I actually quite like the idea of OKRs — sometimes it’s not so obvious how to sift through the soup of things you kind of want, and by explicitly defining an Objective, you’re keeping the main thing the main thing by forcing yourself to figure out what the main thing is.

By simply writing down that your objective is to, say, “learn to speak French” with a key result of “be able to have a conversation in French for 10 minutes”, you've clarified a lot of the ambiguity that would otherwise leave you mindlessly chasing your Duolingo streak forever (without, say, ever speaking to another person in French).

This, though, is the easy part (regardless of how disinclined we tend to be in actually do this). The hard part is trying to figure out how to accomplish that objective.

Input metrics are key — they're your best lever to make efficient progress.

On the one hand, it’s usually straightforward to choose some metrics that indicate you’ve accomplished an objective (what analysts term “output metrics”), but it’s a much harder thing to figure out what you need to do consistently to get there (“input metrics”). Fortunately, as with most things in life, input metrics tend to follow the Pareto principle — most of the value comes from a few key drivers. So the game becomes one of finding those drivers.

For instance, I’ve been trying to get stronger lately. My chosen output metrics are quite straightforward: raw strength on particular exercises at the gym. But after some research and experimentation, I’ve learned that the two input metrics that yield the best results are exertion (measured in number of sets to failure) and protein consumed — not strict adherence to a particular regiment, not total number of sets, not time in gym, not even caloric or macronutrient intake. If I do enough sets to failure and eat enough protein, I get stronger, and if not, I don’t.

If I want to get more serious, of course, I could add more input metrics, but the core tenet here is that prioritizing input metrics according to their importance gives you a strong efficiency lever. I now know that I can spend about 15 minutes in the gym, 4 days a week, and still make progress.

And this is particularly helpful when you have many different objectives — rarely does one live life against a single objective at the expense of all else, after all. Even as a founder, while I’m quite singularly focused on building my company, I have other priorities: I have a daughter and wife that I want to spend time with and make happy, I want to stay healthy, I want to continue to enjoy playing music. Identifying the core input metrics for each activity has been the only way I could possibly make sustainable progress on all fronts that I want to make progress on.

Also, you should track things.

The final point I want to make here is that it’s actually quite useful to explicitly track your input metrics somewhere. In the past, I just used habit trackers or domain-specific apps, but I find that the problem is that the default input metrics are often wrong, and at least for me, my brain will eventually succumb to the vanity metric dopamine hit and undermine my objective. A plain old spreadsheet has actually been quite nice here.

Final comments

I recently had a conversation with a friend (an expert data person) Gordon Wong about all this, and he made the following poignant observation:

“Data is a necessary evil. It’s something we need to reduce complexity.”

This is something I think we’ve missed as our world’s become inundated with more and more arbitrary vanity metrics (think: Goodread books read, standard app streaks): metrics can be powerfully complexity-reducing. Anything you want to accomplish is going to be riddled with your subjectivity and your hopes and your dreams. But metrics have this unique capacity to remove all the cruft by distilling that goal into a single, irrefutable value measurement. And that utility is too often ignored.

P.S. I’m not alone in obsessing over personal data here — look at this Tableau dashboard Gordon made for his health metrics!

Loved the write-up Robert!

The style you've picked up for this type of content is very comfortable to consume.

I particularly like addressing such conversations, these help foster self growth, healthy collaboration, and most importantly boosts confidence towards working in the correct direction.

Would love to have a discussion sometime :)