Money and happiness

What the studies seem to actually say

I’m on vacation, so I’m letting my mind wander a bit. I’ve heard a lot about this idea that money either does or does not buy happiness, so I thought I’d put my academic hat on, read through some literature, and try to come to some sort of conclusion therein. Part of this article is going to be slightly technical, so if you don’t care for the technical side of things, you can skip to “The final conclusion”, where I’ll talk a little bit more about why I think all of this is terrible framing.

Technical discussion: happiness v. money

Literature review

Discussions around the relationship between money and happiness generally cite one of two seminal works:

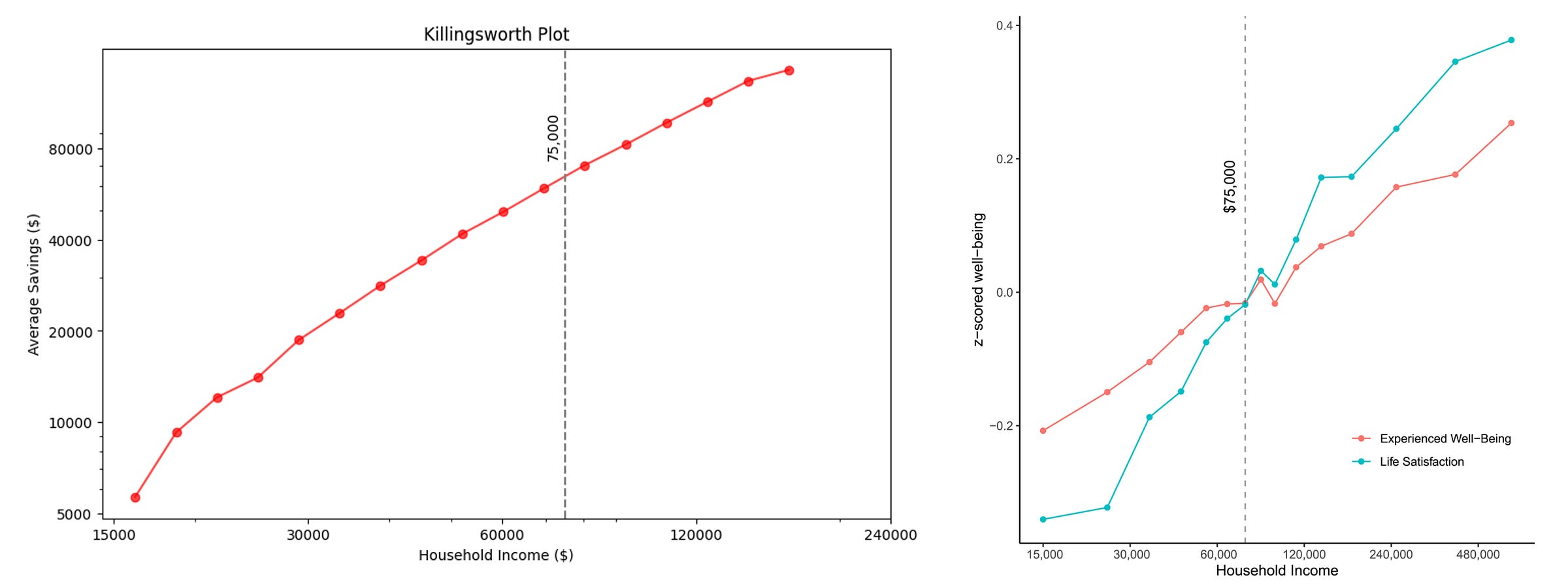

Daniel Kahneman & Angus Deaton’s work, which suggests that “experienced well-being” stops increasing at about ~$75,000 in annual income.

Matthew Killingsworth’s work, which purportedly refutes the above, finding that “experienced well-being” is not so bounded, increasing steadily with household income, without limit. He concludes that “There was no evidence for an experienced well-being plateau above $75,000/y, contrary to some influential past research.”

These are reconcilable

However, the two had different measurement tactics: Kahneman et al. used a binary measurement of well-being, while Killingsworth used a multiple choice one. What’s missing in the discourse, it seems, is that this difference in measurement method makes these two results completely reconcilable, as follows:

More money increases your experienced well-being.

But whether or not your experience of well-being is positive or negative does not change beyond a certain level of income.

And the mechanism that could lead to this is not so hard to see. You can imagine that the question of “how do you feel right now” can be broken down into two questions:

Are you happy?

How happy?

First you choose whether you are happy or not. One might surmise that, above a certain level of comfort, this is more a measure of your subjective inclination towards happiness. I.e. above your needs being met, you do not factor in money when evaluating whether you are happy or unhappy. And so we obtain a harsh cutoff beyond a critical income threshold in answering “are you happy” (which is precisely how Kahneman’s survey phrased the question).

However, with regards to the second question of "how happy are you", one might surmise that you naturally point to how comfortable you feel, how well your needs are met, etc., all of which seem that they would be dependent on the amount of money you make. And so, we obtain a measure of happiness that increases with income without limit (which, again, is how Killingsworth’s survey worked).

A simulated example: “are you saving money?”

To make this a bit more concrete, one can artificially create these two plots by using a trivial example. Imagine if you asked the question “how much money are you saving?” This could be divided into two related questions:

Are you saving money?

How much are you saving?

(And, one can imagine, these two perhaps directly relate to the questions “are you happy” and “how happy are you”, respectively)

We can very simply simulate this out — create a distribution of incomes, a distribution of expenses, and plot the resulting data in these two ways, and put them side by side with the Kahneman / Killingsworth plots.

The Kahneman-style plot still exhibits an asymptote, because the proportion of people saving money doesn’t increase after a certain point.

And, of course, the Killingsworth-style plot continues to increase, because a person’s savings certainly does continue to increase as income increases.

From this, a plausible conclusion we can draw — if both these studies are to be trusted — is that being happy or not is more likely to depend on the existence of disposable income or not. At the same time, the degree of one’s happiness will scale with the magnitude of that surplus. [Colloquially, of course. This is a blog post, not a paper]

The final conclusion

From these studies, one might reasonably conclude that, beyond a certain amount, money is salt. It adds flavor, but not sustenance. Money is great, but it alone is not sufficient. That said, I think the framing of all money vs. happiness discussions are off. In particular, I have two qualms with these studies and their conclusions:

The questions given in the study don’t seem to definitively reflect anything real.

Even if money increases happiness, it’s not clear how important it is.

I’ll briefly touch on these points in this final section.

Are people really happier, or do they just feel like they shouldn’t be unhappy?

For one, “happiness” in these studies is measured with respect to the questions “How do you feel right now?” and “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life?” And it’s not clear whether these questions get to anything meaningful. What do answers to such questions represent?

The value of money seems, of course, blatantly obvious when money is tight—if you are drowning, of course a life jacket changes your answer to the question “how do you feel right now”. But beyond a certain point, the relationship seems tenuous at best. I can buy more things? I feel good about my life in a self-congratulatory way? Or perhaps I just feel more compelled to answer these questions positively, as I have everything I could ever want and more and saying “I am not satisfied” seems childishly unaware.

Money produces happiness, but how much, even?

Moreover, something I find painful about these kinds of articles that highlight some [arguably] causal effect is that it doesn’t really signify how practically important that effect is. I agree that money can make a person feel happier and more satisfied with life. But how important is it relative to other effects? For instance, wisdom seems to far exceed income in predicting one’s life satisfaction, and financial situation seems to be quite inadequate alone.

"Wisdom is the best predictor of life satisfaction in both men and women and can offset the influence of negative age influences on life satisfaction. Wisdom has a greater influence on life satisfaction in older adulthood than health, socioeconomic status, financial situation, environment, or social engagement."

- Beate Muschalla, “Wisdom affinity in the general population”

Academics are careful here, of course, adorning their articles with measured titles. “Experienced well-being rises with income” (Killingsworth). But the insinuations of such a title, even when stated in a measured way, seem obvious, do they not? Experienced well-being rises with income, so we should care about it.

Money as introspection utility; money as optionality

Rather than seeking definitive scientific evidence here one way or another, I find a more useful exercise here is introspection: answer these questions for yourself, then think about why your answers are the way they are. “How do you feel right now?” and “how satisfied with your life?” If you can’t answer positively to either, why not? And if money is a factor, why? Does the ensuing argument hold water, or are you just so used to white knuckling your way to the ends of rainbows that you can’t imagine what any other happiness might look like?

For me, I’ve found that it’s far too easy to pursue money for the wrong reasons. I remember when I was in graduate school, I planned for a career where I’d have a $50,000 post-doctoral salary for, well, almost forever. And I counted myself lucky, knowing that I’d be able to do something I loved and be able to support my family with that income. Of course, I went into tech and my salary ballooned, but the strangest thing happened — I went from having a low salary, which was enough, to having successively higher salaries, which were never enough. I realized that I had a strong tendency to chase money in and of itself, and while the studies I’ve mentioned seem to legitimize this chase, it’s a trap.

While implicit, the framing of these studies therein reinforces a view on life that doesn’t just view money as an augmentation, but as an end in and of itself, supplanting those things that might offer greater meaning. In my opinion, beyond a certain level of base security, money should never be an end in and of itself, but a mechanism by which one can purchase more optionality. That is, with sufficient money, you can choose the next adventure you play.1 And that’s what life is, no? A series of wonderfully unpredictable adventures. And rarely is the end of an adventure the best part of it.

That said, that does not necessarily mean that your next adventure will be any better than the adventures you’ve been on already!

My favorite thing about money is not thinking about it.

You should train an AI advisor with this content