Concepts and conditioning

Let's talk about the gaping singularity at the center of everything that we're evolved to ignore

"Look for your head. Where your head is supposed to be, there's just the world."

Harding, Douglas. On Having No Head.

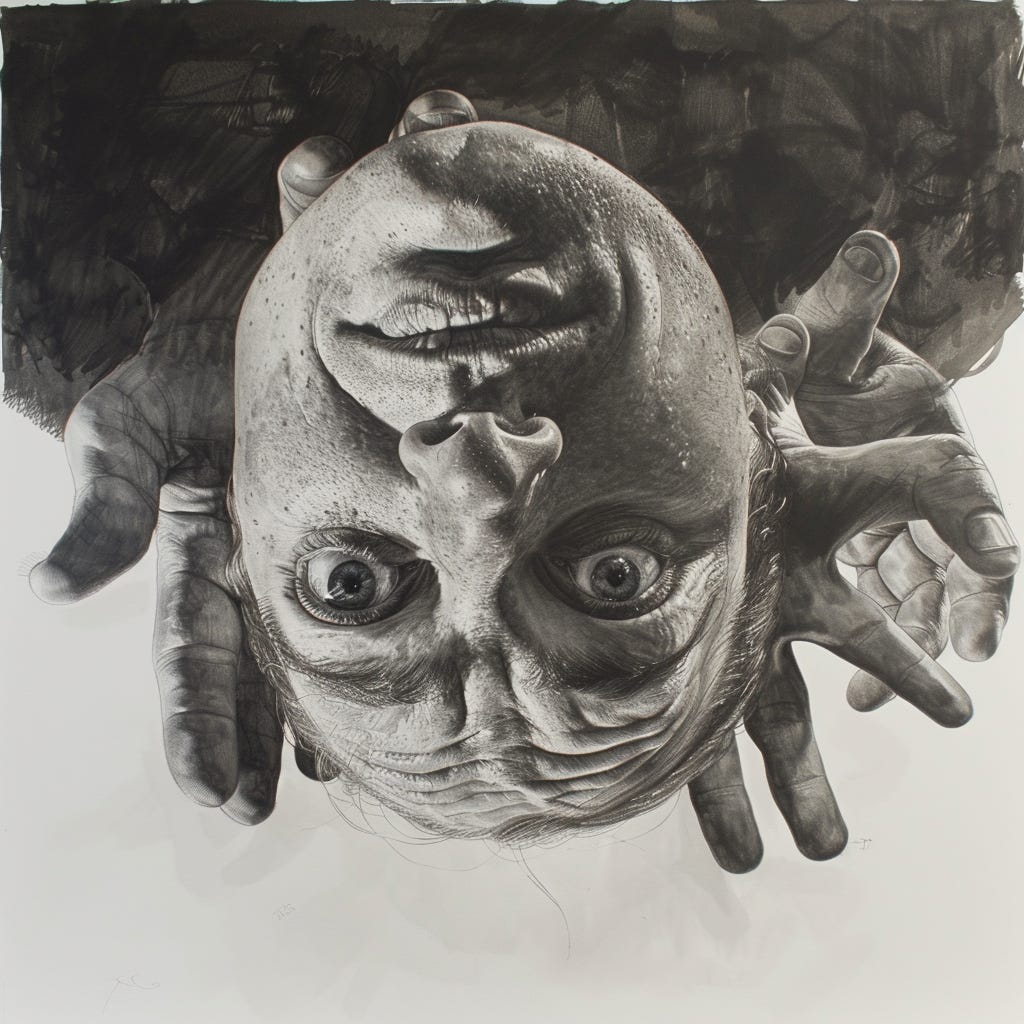

There’s this practice in mindfulness where you try to look for yourself, only to discover that no such sense of self exists. It’s a revelation called nondualism, and Douglas Harding has this wonderful little book where he explores the concept by scrutinizing the headlessness of his existence — that where his head should be, instead he finds only his window into conscious experience. That is: of the ways one can dispel the illusion of self, one such way is to notice that even one’s physical conception of self (a full-bodied human with a head) is a construct that differs quite greatly from the reality of one’s experience as that physical self (in which one can not directly see one’s head, except by extrapolation)…

… what I found was khaki trouserlegs terminating downwards in a pair of brown shoes, khaki sleeves terminating sideways in a pair of pink hands, and a khaki shirtfront terminating upwards in - absolutely nothing whatever! Certainly not in a head.

Harding, Douglas. On Having No Head (p. 6).

Hilarity of this description aside, it represents an experience in mindfulness meditation that I’ve always found a bit arcane, but as I’ve recently come to understand it a bit better, I want to spend some time talking about it.

Progress in nondualism: looking for my hands

Certainly, cerebrally (haha), it’s easy to see that there is no trace of your head in your visual field when looking out from it, but it’s quite unclear what the significance of such a revelation is. At best, in trying to practice this, I’d often glimpse a brief impression that there is nothing there where my head (and so, my sense of self) should be. That my self is just a construct that I have assigned to this signature of feelings that are arising in consciousness: the edge of my nose, the thoughts that arise, the illusory feeling that those thoughts originate and exist within me. But quickly, the glimpse would dissipate and I would no longer be able to disentangle myself from the dual nature of reality — there’s me, and then there’s the world.

Of course, this is quite difficult to internalize, but I recently came to an exercise that helped make this stick longer for me. I started by noticing the same headlessness exercise could be applied to my hands.1 And then I subsequently listed out the things that I felt described my hands. The pinkness of my flesh, the visual boundary between the hands and everything else, the sensations that I felt within them, the quickness and automaticity of their actions. And, while this is certainly more visceral for the head, I realized that a large part of myself was embodied in these hands, but they were not me. They are an abstraction that sits over all the things that I perceived them to be, alongside decades of conditioning and muscle memory that has blurred the line between their individual signatures within my consciousness and the higher-order sense of them that my mind interacts with, almost unthinkingly.

It’s all concepts, even your sense of self

This may sound as abstract as the whole headlessness ordeal, but it was a breakthrough for me simply because I had another pattern by which to see my headlessness — headlessness is, too, a sense of concepts and muscle memory tied to them, just far more strongly engrained. So, too, is one’s internal impression of self (what I tend to call my “soul”): there’s all the conditioning I have around how my thoughts invoke action; then there’s this extremely strong illusion that my thoughts are me — a deep, deep concept layered on top of the thoughts themselves.

And this observation extends beyond one’s sense of selflessness — we tend to layer everything as humans. All of our knowledge and understanding is just layers on layers on layers. Concepts on concepts on concepts. We hide the inherently intractable nature of raw experience under the lossy story that we are telling ourselves about it. We layer definitions over the physical world, burying the ineffability of those concepts beneath an intricate network of facts and abstractions. We humans are somehow experts at dealing with these abstractions, cataloguing definitions alongside intuition paintings in our minds, hardening this connection until you can believe in the illusion strongly enough that you can reason around it. And our muscle memory — our conditioned habits and thoughts in response to these concepts layered over stimuli — is culpable in perpetuating this illusion. Recognizing all this has been a fun way to see almost everything with fresh eyes, from aspects of my consciousness to my relationship with words. We are so well-acquainted with our lives that we forget that almost all things are almost inherently unknowable.

“The particular shade of color that I'm seeing may have many things said about it. I may say that it is brown... But such statements, though they make me know truths about the color, do not make me know the color itself any better than I did before.”

- Bertrand Russell, on color, purportedly

As an example exercise: go pick up a book you want to read later today. On the one hand, your mind has deep-etched pathways for figuring out what book to read, and your body knows how to contort itself to find that book. But you’re also unknowingly dealing with a whole host of concepts all at once — your sense of self, in that you are doing the thinking and the searching, of course. But also what a “book” is. What it is to “want”. What it is to “read”. And deep in this cavern I find there are three things: (1) my open conscious awareness, being buffeted by (2) a slew of conditioned behaviors, interacting with (3) layers of useful concepts.

This has had two points of particular utility for me as of late:

On the one hand, the meditative exercise is quite nice on its own. The formerly stochastic, serendipitous process of evoking nondualism is becoming steadily more repeatable to me: halt the muscle memory, break down the concept, observe its constituents. We’ve layered two things over ourselves: concepts and conditioning. But on trying to identify the things in our heads that are and are not those things, I find myself face-to-face with the totality that is my consciousness.

I’ve always had a really hard time catching my thoughts before they happen. But even just having the label “conditioning” in my vocabulary to describe what’s happening in my brain has helped me finally feel the tether before I’m pulled along (though I admit, the timing may be entirely coincidental). In particular, I’ve been able to notice lately what happens when my mind is being creative, which often pulls me quite quickly out of meditation practice. I’ve noticed lately that there’s a physiological signature first, where I’ll feel a building muttering in the back of my head or a rising excitement in my chest or, for lack of a better description, this widening feeling in my brain. And then there’s this conditioned response to that feeling — a narrowing of my focus (the entire world falls away). It usually starts with a few seeder words, then it’s almost as if my eyes don’t see anymore — the words act as a sort of sorcery, quickly invoking images of a rich world that those words paint in my head.

I think it’s quite easy to forget that this whole thing — the miracle of just being here in this moment, let alone reasoning with higher order layers on top — is absolutely wild, and this has all been this very arduous exercise in re-internalizing that absurdity. Still, I’d highly recommend it.

"If I fail to see what I am (and especially what I am not) it’s because I’m too busily imaginative, too “spiritual”, too adult and knowing, too credulous, too intimidated by society and language, too frightened of the obvious to accept the situation exactly as I find it at this moment.”

Harding, Douglas. On Having No Head.

This week

One final note: If the above was confusing but you want to get started, I really love ’s meditations on this topic from his Waking Up app — here’s a recent one I found particularly compelling.

I really love this post from . I know my post above might seem a bit esoteric to some of you, but he very nicely describes some of the states that mindfulness practice bring you to, and they are quite compelling.

I also recently have been reading some of ‘s work. He seems to embody a wonderfully similar worldview to my own, so give him a read if you have a minute. He touches on topics like the above every so often.

I love that you're going down this rabbit hole. It is a fascinating and (apparently) endless inquiry.